- Calls to this hotline are currently being directed to Within Health, Fay or Eating Disorder Solutions

- Representatives are standing by 24/7 to help answer your questions

- All calls are confidential and HIPAA compliant

- There is no obligation or cost to call

- Eating Disorder Hope does not receive any commissions or fees dependent upon which provider you select

- Additional treatment providers are located on our directory or samhsa.gov

Emotional Eating and Bulimia Nervosa

Contributor: Sabrina Dotsenko MSH, RD, LDN, Registered Dietitian and Kate Clemmer, LCSW-C, Community Outreach Coordinator for The Center for Eating Disorders at Sheppard Pratt

What is Emotional Eating?

A generally accepted definition of emotional eating (EE) is eating in response to negative affect or using food to dull or avoid difficult feelings. Most people have experienced this to varying degrees at some point in their lives. Because food can temporarily help to soothe or distract us, EE may become a conditioned response to elevated stress or strong emotions.

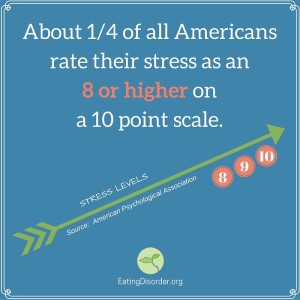

Recent research is looking at the biology behind all of this, specifically that which involves individuals’ cortisol and ghrelin levels. Cortisol is a hormone that increases appetite and is produced by our bodies in response to chronically elevated stress levels. Elevated cortisol may be one reason why high-stress is associated with EE, overeating and obesity.

Another hormone, Ghrelin, also plays a role in appetite regulation. Ghrelin levels naturally rise to stimulate hunger, motivate us to eat, and then fall once a person begins a meal.

This decrease in ghrelin acts as a satiety cue, in other words it helps us to feel full and stop eating. Studies show baseline ghrelin levels are lower in emotional eaters and the natural decline of ghrelin after consumption was not apparent among emotional eaters meaning they did not experience satiety or fullness in the same way as their non-emotional eating counterparts. [1]

Other important findings from EE research include the following:

- Individuals who show increased food intake in a negative emotional state also tend to overeat in response to other cues such as a positive emotional state. [2]

- Thayer (2001) cites feelings of increased tension and low-energy, or “tense tiredness,” as the primary culprit in EE, as it underlies many of the negative moods (depression and anxiety) that have been found to be associated with overeating. [3]

- Approximately 10-60% of children and adolescents report emotional eating with higher estimates in adolescent samples and weight-loss treatment-seeking populations. [4]

- The specific negative affect that most leads to EE is different during adolescence. Researchers suspect it could be that stress and confusion are experienced more by adolescents, while depressed mood and fatigue are experienced more frequently in adults. [5]

- Gender stratified analyses of adolescents revealed significant associations of perceived stress, worries and tension/anxiety to EE for girls, while only confused mood was related to EE in boys. [5]

Psychologist and author Susan Albers recently summarized EE by saying, “Every day researchers are continuing to unravel the biological mechanisms (hormones, chemicals, etc.) that lead us to emotional eating.

Psychologist and author Susan Albers recently summarized EE by saying, “Every day researchers are continuing to unravel the biological mechanisms (hormones, chemicals, etc.) that lead us to emotional eating.

For now, what we do know for sure is that emotional eating does work to soothe your feelings temporarily–but it spirals into more problems and issues when done too frequently or when it is the only thing that makes you feel better.” [6]

Emotional eating, while potentially problematic, is not an official eating disorder diagnosis. It can however play a role in the development of serious eating disorders like Binge Eating Disorder and Bulimia nervosa.

What is Bulimia Nervosa?

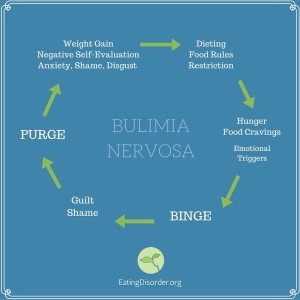

Bulimia nervosa (BN), is a serious illness defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. It involves recurring cycles of excessive food consumption – binges – followed by compensatory behaviors (such as self-induced vomiting, laxative abuse or over-exercise) in an attempt to counteract the calories consumed and subsequent presumed weight gain.

During a binge, there is a sense of loss of control. In other words, the individual has a desire to stop eating but feels unable to do so. In bulimia, self-worth and self-evaluation are disproportionately based on body size and shape.

It’s easy to see how someone who is prone to EE may be at risk for the development of bulimia. Individuals with bulimia often report experiencing strong negative emotions prior to a binge.

It’s easy to see how someone who is prone to EE may be at risk for the development of bulimia. Individuals with bulimia often report experiencing strong negative emotions prior to a binge.

While food may provide temporary relief from an uncomfortable emotional state, the binge itself ultimately heightens feelings of guilt, shame and disgust.

In turn, these emotions can trigger compensatory behavior and perpetuate a dangerous cycle (left).

The restrict-binge-purge cycle is influenced by both biological and emotional factors. The body adjusts to purging and restriction by slowing metabolism which causes weight gain. Weight gain triggers negative self-evaluation and thus, more dieting/restricting.

Dieting increases a person’s risk for bingeing which, given the slower metabolism, is more likely to lead to weight gain. If uninterrupted, the cycle continues.

How are bulimia and emotional eating connected?

Not all individuals who struggle with emotional eating will develop an eating disorder but all individuals with eating disorders do likely struggle with EE. Here’s what the research says:

- One study [1] that looked at the role of emotional states in eating behaviors concluded that “emotional eating is a relevant psychopathologic dimension that deserves a careful investigation in both anorectic and bulimic patients.”

- Individuals with eating disorders do score higher on the Emotional Eating Scale (EES) when compared to those without eating disorders [7]

- Emotional eating has been identified as a possible factor triggering binge eating in bulimia [7]

- Emotion dysregulation, or the inability to control and modulate one’s affective state, has also been identified as a risk and maintenance factor in bulimia [8]

Thus, the role of emotions, and how individuals regulate and cope with them, is an important part of prevention and intervention for both EE and bulimia. More research, taking into account the hormonal influences discussed earlier, is needed into this complex relationship.

What Helps?

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is recognized as the standard frontline treatment for bulimia nervosa, while Interpersonal Therapy (IPT) and Dialectic Behavior Therapy (DBT) have also been shown to be effective.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is recognized as the standard frontline treatment for bulimia nervosa, while Interpersonal Therapy (IPT) and Dialectic Behavior Therapy (DBT) have also been shown to be effective.

Individual support from a Registered Dietitian (RD) trained to treat eating disorders is also recommended. Many of the interventions for someone with BN can be helpful for individuals struggling with EE. An RD can help in the following ways:

- Developing a structure and routine with meals

Many individuals with eating disorders describe their hunger or fullness cues as being absent or not being able to fully recognize them until they are at an extreme. When you are overly hungry you are at risk for overeating. When you eat past fullness you are at risk for purging. Working with an RD to ensure adequate intake and consistency with meals is an integral part of re-establishing and reconnecting with your body’s natural hunger and fullness cues.

- Practicing mindful eating

It is important to develop a routine with meals to help re-calibrate physical hunger and fullness cues, but it is equally important to work on self-monitoring. This is the act of being attentive to your body, your food and your feelings. For example, are you eating because you are bored or because you are hungry? Are you not eating because you are physically satisfied or because you are fearful about a particular food? Dietitians and therapists can help you find ways to monitor behaviors, thoughts, situations and feelings at meals. This is an opportunity to note emotional hunger vs. physical hunger and how your body and mind respond. - Being flexible, patient, and compassionate with oneself

This is probably one of the more challenging aspects to work on but it is important for recovery in the long term. Many individuals want to heal immediately, but in reality it takes time to change behavior and there is no perfect recovery. There are going to be successes and there are going to be challenges along the way to a healthy relationship with food. Normal eating doesn’t mean you never eat for reasons other than physical hunger, it means you are aware that you may be eating in the absence of hunger and you are kind to yourself when it happens. Be the detective (mindful) and the student (always learning) but not the judge.

About the authors:

Sabrina Dotsenko MSH, RD, LDN, Registered Dietitian

Sabrina Dotsenko received her Bachelor of Science degree in Health and Nutrition from the University of North Florida in Jacksonville. She continued on at the university to complete their dual program for her dietetic internship and a Masters of Science in Health with emphasis in Nutrition. Sabrina has experience in a variety of healthcare settings including acute care hospitals and outpatient clinics. She joined The Center for Eating Disorders at Sheppard Pratt in the summer of 2013. Sabrina’s role at the Center includes providing individualized nutrition assessments, counseling and education for the outpatient population. She guides patients toward improved eating disorder symptoms and to rebuild trust with food through nutrition interventions.

Kate Clemmer, LCSW-C, Community Outreach Coordinator

Kate Clemmer, LCSW-C, Community Outreach Coordinator

Kate Clemmer earned her Master of Social Work degree from the University of Maryland, Baltimore in 2005 with a focus on Management & Community Organization and a specialization in Child, Adolescent & Family Health. Before joining The Center for Eating Disorders at Sheppard Pratt in 2008, Kate provided school-based therapy to adolescents and families in Baltimore City and coordinated a multi-school health education and prevention program. As the CED’s Outreach Coordinator, Kate currently facilitates trainings and workshops in the community, provides outreach to individuals and families and coordinates the Center’s annual community events. These events include an annual Symposium for health professionals, the Love Your Tree Body Image Campaign, and National Eating Disorders Awareness Week. Kate also facilitates the Center’s community support group for individuals with eating disorders and their friends/family, held on Wednesday evenings.

References:

1. Raspopow K, Abizaid A, Matheson K, Anisman H. Anticipation of a psychosocial stressor differentially influences ghrelin, cortisol and food intake among emotional and non-emotional eaters. Appetite (2014) 74:35 [PubMed]

2. Bongers P, de Graff A, Jansen A. ‘Emotional’ does not even start to cover it: Generalization of overeating in emotional eaters. Appetite (2015) 10;96: 611-616

3. Thayer R. Calm Energy: How people regulate mood with food and exercise. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001.

4. Vannucci A, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Ranzenhofer LM, Matheson BE, Cassidy OL, Zocca JM, Kozlosky M, Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Construct validity of the Emotional Eating Scale adapted for children and adolescents. International Journal of Obesity. 2012;36: 938–943. [PMC free article]

5. Nguyen-Rodriguez ST, Unger JB, Spruijt-Metz D. Psychological determinants of emotional eating in adolescence. Eating Disorders. 2009;17:211–224. [PubMed]

6. Albers S, 5 Fascinating Things You Didn’t Know About Emotional Eating. Huffington Post; 2015. Available Online.

7. Ricca V, Castellini G, Fioravanti G, Lo Sauro C, Rotella F, Ravaldi C, et al. Emotional eating in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53:245–51. [PubMed]

8. Selby E. A., Doyle P., Crosby R. D., Wonderlich S. A., Engel S. G., Mitchell J. D., et al. (2012). Momentary emotion surrounding bulimic behaviors in women with bulimia nervosa and borderline personality disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 46, 1492–1500. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.014 [PMC free article]

The opinions and views of our guest contributors are shared to provide a broad perspective of eating disorders. These are not necessarily the views of Eating Disorder Hope, but an effort to offer discussion of various issues by different concerned individuals.

We at Eating Disorder Hope understand that eating disorders result from a combination of environmental and genetic factors. If you or a loved one are suffering from an eating disorder, please know that there is hope for you, and seek immediate professional help.

Last Updated & Reviewed By: Jacquelyn Ekern, MS, LPC on January 20, 2016

Published on EatingDisorderHope.com

The EatingDisorderHope.com editorial team comprises experienced writers, editors, and medical reviewers specializing in eating disorders, treatment, and mental and behavioral health.